Rostand Medeiros – https://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rostand_Medeiros

Adventures and epics at sea have always attracted general interest, and this is a very ancient fascination. Narratives about the elements of maritime nature are almost always worth reading. But typically, the protagonists of these incredible feats are men.

And if a woman were the protagonist of a genuine and gripping sea story, would her accomplishments be equally appreciated in today’s society?

It doesn’t seem like it to me!

To my surprise, this remarkable woman, with an incredible story of survival at sea, is largely forgotten in her own country. And it is a country known for highly valuing its own history.

And look, at the time the events happened, she was only 19 years old and pregnant with her first child. But that did not prevent her from taking over as the captain of a large sailboat after her husband, the captain, became seriously ill. She did this in the midst of the treacherous storms of Cape Horn and the Drake Passage, which included extremely cold temperatures, giant waves, hurricane-force winds, and many other challenges. She also faced a tyrannical first officer and a crew that attempted to mutiny. However, she overcame fatigue, fear, and pain, and managed to reach her destination.

This is your story!

A Woman of the Sea

In the northeastern United States, in the state of Massachusetts, lies the great city of Boston. Just in front of it is the city of Chelsea, a place that has had a strong connection with the ocean since its early days. In the mid-19th century, Chelsea developed as a significant industrial center for sailboat construction, establishing itself as a powerhouse in this sector in the United States. This led to the city attracting skilled workers from all over the country. And it was in this city where, in the first decades of the 19th century, the English couple George and Elizabeth Brown arrived.

George was a professional sailor, experienced with many years at sea. In the new city, he quickly became involved in maritime activities. Isabel, as was customary in the 19th century, had the sole objective of her life to care for her home and her children. Even more so as the wife of a sailor, she was often away from home, sometimes for years.

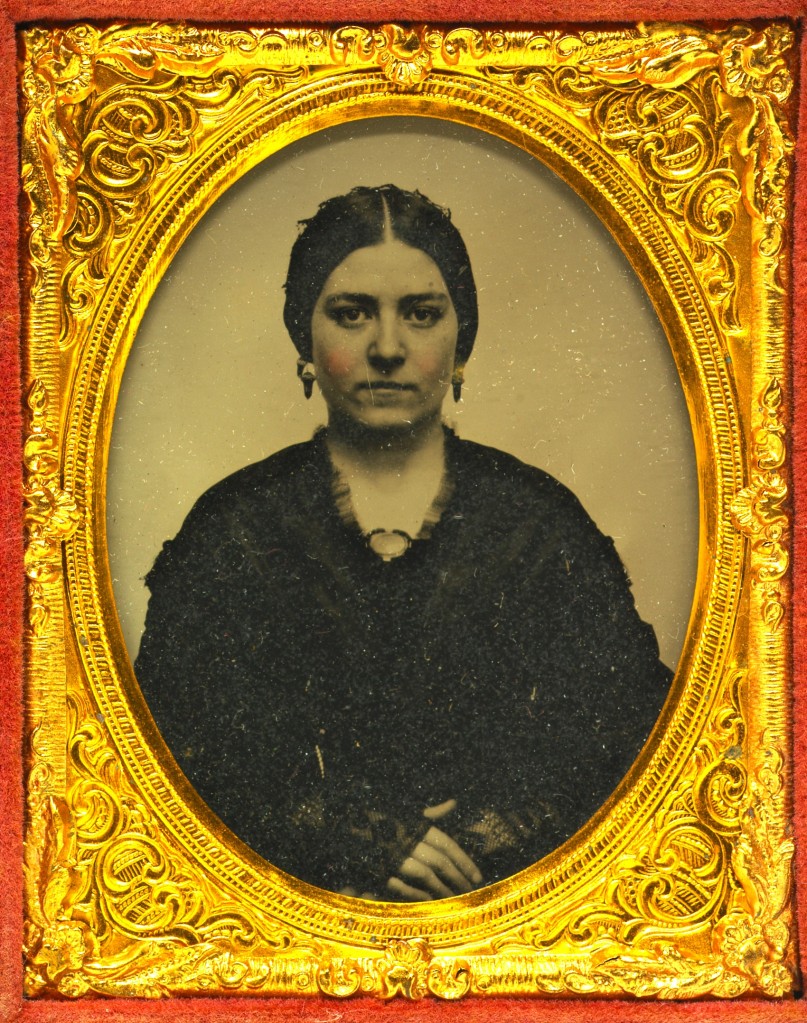

But these absences did not prevent George and Elizabeth from creating a large family, whose children were connected to the sea. In this era, it was not surprising that Mary Ann Brown, born in 1837, married at the age of 16 to Joshua Patten, a charming sea captain who was nine years her senior. Mary Ann was described as a beautiful young woman with attractive features, refined and graceful manners, a slim and petite figure, long dark hair, and vibrant brown eyes.

Joshua worked at the helm of sailboats, transporting cargo and passengers from New York to Boston. But he was a rising star among ship captains, so it was no surprise when he was offered the command of a sleek and powerful Clipper.

This type of ship emerged as trade and the global economy expanded. Basically, it was a type of fast-loading sailboat that originated in the United States and had its heyday in the mid-19th century. The most striking features of the ship were its well-cut bow, narrow width in relation to its length, and high achievable speeds. These features resulted in limited cargo space in favor of speed. The masts, posts, and frames were relatively large, and additional downwind sails were often used. This type of vessel requires a large number of experienced and well-prepared crew members and commanders. Joshua Patten was one of them!

A Woman on Board

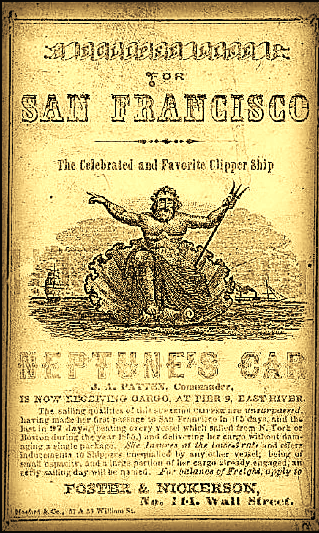

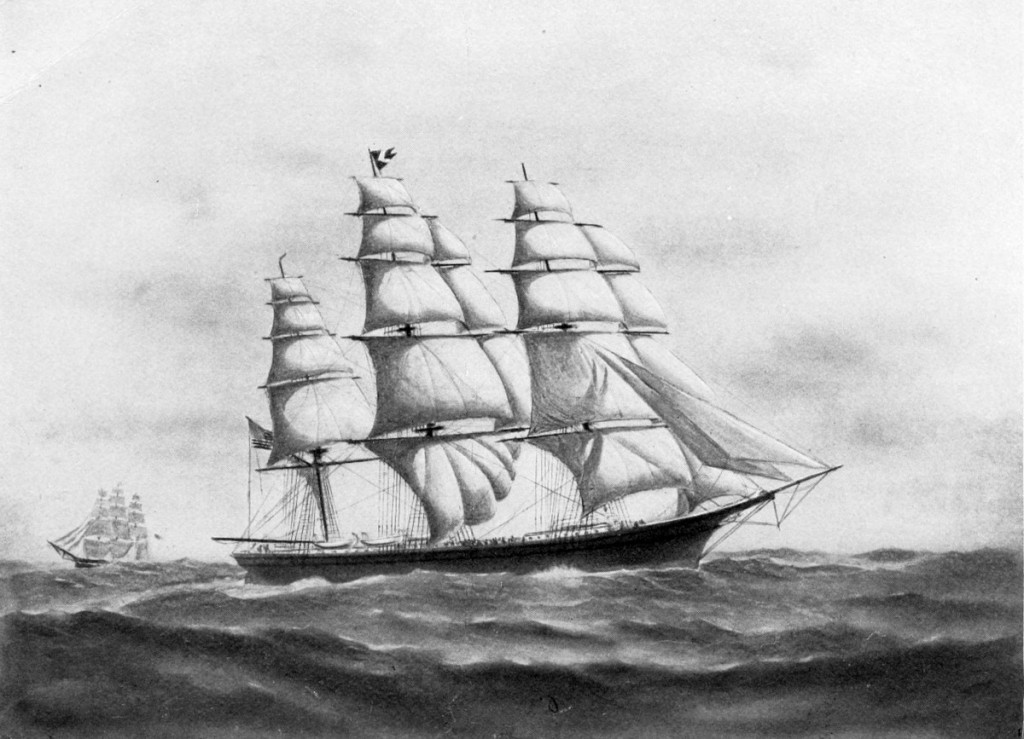

He was assigned a sailboat weighing more than 1,600 tons, with massive sails, and named Neptune’s Car.

This ship was launched on April 16, 1853, at the Page & Allen Company shipyard in the city of Portsmouth, Virginia. It was later acquired by the transport company Foster & Nickerson’s line from New York. In its time, Neptune’s Car was considered a long and elegant boat. It was 68 meters long, had a beam of 12 meters, and could carry 1,616 tons of cargo. She had three tall masts and carried 25 sails, the largest of which was approximately 70 feet in diameter. A true colossus of its time.

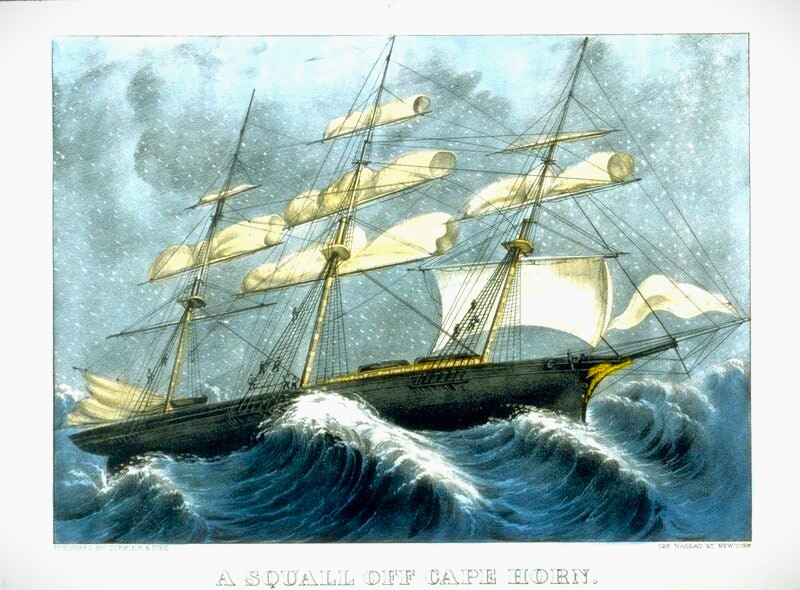

Among the main destinations reached by the fast Clippers were the North American city of San Francisco, on the west coast of the United States. The problem was that, before the Panama Canal, the only way to reach there by sea was to depart from a port on the east coast, with New York being the main one, and sail south along the entire coast of North America.

And from the south, crossing the treacherous Cape Horn and the Drake Passage, entering the Pacific Ocean, then tracing the entire South American coastline in a northerly direction, passing along the coast of Mexico, and finally reaching San Francisco. A trip lasting four months and covering approximately 24,000 kilometers. Despite the challenges and obstacles, this route played a crucial role in supporting the booming economy driven by gold mining in California. Shipping companies stood to make enormous profits by delivering food and supplies to the area promptly.

Neptune’s Car had successfully completed its first voyage between New York and San Francisco, with navigation proving to be successful. However, the relationship between the crew left something to be desired. Among the problems that occurred with the commander and the crew, there was no shortage of threats of mutiny. The captain warned that he would shoot anyone who dared to carry out such an idea. Evidently, everyone on board went to the street, and Joshua Patten was called to take command.

Soon, Lady Mary Ann Brown Patten insisted on joining her husband on his first voyage as the captain of Neptune’s Car. She had an opportunity that few women of her time would get: to see the world aboard a ship.

They traveled to the southernmost part of the American continent and entered the Pacific Ocean before reaching San Francisco. From this city, a new cargo transport job emerged, and they went to Shanghai, China, where they shipped a large quantity of tea destined for London, England. They returned to the Atlantic Ocean by navigating the treacherous Cape Horn on their way to their destination. They spent several months together at sea before returning to New York, Boston, and Chelsea.

Although women crewing ships was very rare at that time, it was not uncommon for the wives of commanding officers to be present on cargo ships. In the 19th century newspapers, it was common to find news articles on the National Library website about ships anchoring in the port of Rio de Janeiro. These articles would mention the ship’s name, tonnage, cargo, captain, crew members, and even highlight the presence of the commander’s wife, which the newspapers often praised.

Normally, during navigation, the wives of these officers would stay in their cabins, engaging in activities such as reading, knitting, or playing a musical instrument befitting of modest ladies. They would occasionally come out to get some fresh air and accompany their husbands on leisurely walks through the ports of destination.. But for Mary Ann Potter, staying on board would be different.

She didn’t want to merely be the “captain’s wife.” She was determined to be useful and learn everything she could to assist her husband on board the Neptune Car.

It is said that Mary Ann spent her time searching the ship’s small library, reading about the rudimentary medicine of her day, and assisting sailors with their ailments. Joshua, in turn, helped his wife in her quest for knowledge by teaching her the basics of navigation, meteorology, ropes, sails, and other duties of sailors. He also taught his wife how to navigate using equipment such as a sextant, compass, astrolabe, and navigation charts. Despite facing certain financial limitations, Mary received the necessary support from her family in Chelsea to receive an excellent education. She demonstrated no difficulties in grasping complex technical concepts.

What no one aboard the Neptune Car had any idea of was the future usefulness of these teachings.

And it would be a very problematic future!

The Greed of the Unclean

In July 1856, Neptune’s Car was preparing for its second voyage with Captain Joshua in command. Mary Ann would accompany her husband, but she was pregnant with her first child. But only she and Joshua shared this secret. They probably believed that there would be enough time to travel from New York to San Francisco, and that the child would be born in Chelsea upon their return. A somewhat risky idea.

Well, we know that at that time, women were taught to consider themselves and act as the “weaker sex,” and that they should always protect themselves to avoid problems. But I think Mary Ann missed that class!

The problems soon began.

During the charge, there was an accident, and Joshua’s loyal first officer broke his leg. Financiers Foster & Nickerson, eager to waste no time, placed an inexperienced young man named William Keeler in this delicate position. Something reckless, because after the commander, he was the first officer who made all the decisions on a ship.

The problems continued when Joshua began to feel unwell due to an unknown illness, which would only worsen his condition later. But Foster & Nickerson, a pair of ambitious and heartless capitalists, disregarded their employee’s predicament and cast him into the sea with Keeler.

The main reason for all this rush was that Foster & Nickerson didn’t just want to make a profit from the delivery of cargo. They placed a substantial wager against the owners of three other Clippers ships that were scheduled to travel the same route from New York to San Francisco, all departing simultaneously. Since the Neptune Car was still a relatively new ship, they wanted to demonstrate its capabilities and ensure that it would be the first to reach its destination port. It is true that the winning captain could earn between $1,000 and $3,000, which was considered a fortune at the time, if he completed the voyage first. Despite the encouragement, in fact, the Foster & Nickerson line followed the ancient tradition of wealthy individuals who were willing to risk the lives of their employees in order to outdo other wealthy individuals.

So off they went, and Joshua entrusted Keeler to stay the course while he tried to rest and recover with the assistance of his wife. But Keeler proved himself to be an incompetent idiot in no time at all. His list of infractions is impressive: he slept through half of his shifts, navigated courses through coral reefs, required orders for simple tasks, and ultimately, he outright refused to perform certain tasks with the sailors, such as raising sails. About a month after sailing from New York, Commander Joshua locked himself in his cabin.

The ship was far south and was now facing constant gales of snow and hail. None of the other crew members were able to handle the navigation. The second officer was illiterate, and the third was another idiot who happened to be a friend of Keeler.

Captain Joshua had to stay awake day and night to maintain the correct course. Because of this, he increasingly relied on Mary Ann to help him confirm her position, course, and speed. He acknowledged that she was a better mathematician than he. When the large ship reached the Strait of Le Maire, a narrow maritime passage between the Island of the States and the easternmost part of Tierra del Fuego, Argentina, the captain’s condition worsened. He developed a fever, became delirious, and eventually became incapacitated in his cabin. Mary Ann then took charge for the first time.

If the problems were already enormous, to complicate things even further, Mother Nature seemed determined to attack that sailboat with all her might. At Cape Horn, the Neptune Car was rocked by fifty-foot waves and winds reaching speeds of 100 miles per hour. The sky darkened, transforming into a swirling mass of clouds, wind, and rain. Unsure of her exact location, Mary Patten decided that her only chance of survival was to temporarily deviate from the shortest course and head west, in anticipation of more favorable conditions. She then steered the ship towards the south-southeast, sailing with the wind. Thus, the Neptune Car quickly escaped the dangers of Cape Horn.

But the biggest threat was still that despicable Keeler.

Captain Mary Ann

Upon learning of the captain’s poor health, he sent Mary a letter offering to assume command if she released him. Given the extreme seriousness of her husband’s situation, she initially accepted the offer. Keeler kindly offered to relieve her of the burden and take control himself. But Mary Ann responded that she could not accept this condition since they had many problems as a couple. Keeler then attempted to incite the crew to mutiny, but fortunately, they refused.

The captain’s condition improved somewhat, and he agreed to let Keeler take the helm to relieve his wife of her duties. He may not have believed in Mary Ann’s abilities, but her condition was also complex. Regardless of this issue, it quickly became evident that it was a significant mistake.

First, due to the captain’s illness, Keeler prohibited Mary Ann from going on deck to take navigational measurements. Then, for reasons still unknown to those who investigated the matter, the first officer began secretly steering the ship towards the Chilean port of Valparaíso, despite explicit orders to go directly to San Francisco. However, he did not possess the competence of the sole woman on board.

Mary Ann, despite being largely confined to the dormitories, noticed that they were veering off course. And to prove it, she set up a basic compass in the captain’s quarters and demonstrated the situation to Joshua. Upon confirming the action and with thousands of dollars’ worth of valuable machinery and supplies for the California gold mining fields on board the ship, the captain ordered the first officer to be confined again, following a heated argument with Mary Ann.

But this was too much for Joshua. The captain developed pneumonia, which only complicated the undiagnosed illness he had at the beginning of the trip: tuberculous meningitis.

Mary, who was still in the sixth month of pregnancy, took full control of the ship. Despite her intellectual disabilities, she received support and assistance from the second officer. The Neptune Car continued to move forward through deadly storms that rocked the ship. Meanwhile, Joshua’s situation became increasingly worse. The infection had spread to his brain, causing him to become delirious, blind, and partially deaf.

Meanwhile, given the situation, Keeler attempted to convince the crew to join him in a mutiny against Mary Ann Patten. He heard the terrible rumors about the conspiracy and feared that desperation would make the crew vulnerable to his control. She couldn’t let that happen. The Dayle Tribune of New York later reported, “Mrs.” Patten gathered the sailors on deck and explained to them the dire situation of her husband, while also requesting their support for her and her second mate. Each man responded to her call with a promise to obey all of her orders. The incomparable Mrs. Patten now directed all movements on board.

Now, Captain Mary Ann Patten warned Keeler that she would report him to the San Francisco authorities for attempted rioting, and he would be sent to jail. It is worth noting that at that time, the most common sentence for mutineers was death by hanging.

Mary later commented that she spent 50 days wearing the same clothes, with minimal time for personal hygiene, amidst extreme stress, surrounded by a challenging team and a very ill husband. She felt the need to take charge of the ship and stay informed about everything that was happening at all times.

Finally, four months after leaving New York, the ship arrived in San Francisco on November 15, 1856. Mary Ann took command and guided the ship to the dock. In total, she was alone in command of the ship for 56 days.

The spectators at the port were surprised. The ship’s second officer shouted for help to lift Captain Patten onto a stretcher. The proud captain looked thin and frail, with a pallid gray face. The dockworkers were even more curious about the presence of a delicate-looking young woman among the crew of men, giving orders. Judging by the roundness of her belly, it was evident that she was approximately six months pregnant. Despite this, she remained by her husband’s side as he was transported to the hospital. Soon, the news spread by word of mouth throughout San Francisco.

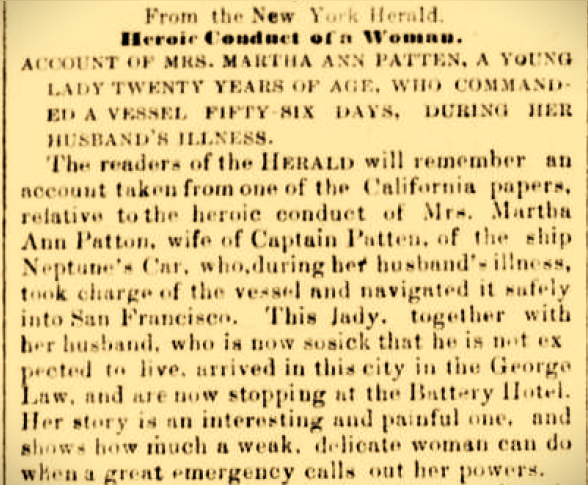

When the press learned how she managed to command a powerful Clipper, take care of her husband, protect the ship and cargo, and control the rogue first officer, all at the age of 19 and while pregnant, Mary Ann Patten became an instant celebrity. Newspaper after newspaper interviewed her.

Newspapers around the world, including those as far away as London, began reporting this news. Eager journalists began piecing together the sad yet inspiring story. Meanwhile, she discovered that her boat had even come in second place in the “Clippers Race of 1856,” something she was not prepared for. Arriving in San Francisco, Ella Mary became a national sensation.

It turns out that Captain Joshua Patten was a Freemason, and to support him during his illness, they received significant assistance from the California Masonic Temple. They also received support from Freemasonry to return aboard a ship, the George Law, which would take them to New York and then to Boston.

In New York, a journalist from the New York Daily Tribune (page 5, 02/18/1857) commented that the couple was staying at the Battery Hotel. It was mentioned that Joshua was carried in a litter from the ship to the hotel by his Mason brothers. And that his condition was “delicate.” So delicate that the journalist, without any sense, stated that Mary Ann “would soon be a widow.” Even in connection with Freemasonry, where Joshua Patten was before coming to Boston, he received the support of the Masonic brothers.

While the couple returned home, William Keeler never went to prison or faced execution. Still aboard the Neptune Car, he escaped with the assistance of a companion and vanished. He must have changed his name and, who knows, become a gigolo in a Wild West tavern, or a horse thief, or a loan shark, etc.

The Early End of a Sea Warrior

After arriving in Boston and Chelsea, despite the media attention, she encountered a problem with her husband’s company. Even though Mary Ann was pregnant and her husband was very ill, Foster & Nickerson adamantly refused to pay Joshua his salary and bonuses. They claimed that he had handed over the ship to someone “without any training or experience.” They remained stubborn until the end and never paid a single cent, despite the fact that the captain clearly deserved it.

Mary wrote a letter to the insurance company, Atlantic Mutual Insurance Company, explaining what had happened during the trip. It was only after a public outcry that the company awarded Joshua a $5,000 bonus and showed its magnanimity by sending Mary Ann $1,000. Prize of the year. Anyway, the cargo he saved was worth $350,000.

Journalists who followed the story were not impressed by the “generosity.” The New York Daily Tribune of April 1, 1857 sarcastically proclaimed, “One thousand dollars for a heroine… from the charitable and grateful hands of eight insurance companies with capitals large enough to insure a navy…”

Being an educated woman of the 19th century, she wrote to them to sincerely thank them and asked them to also acknowledge the crew members of Neptune’s Car who had supported her and her husband. And as a Victorian woman, she downplayed her own role, stating that she was “merely fulfilling her duties as a wife for the sake of her husband.”

A Boston newspaper launched a campaign to cover the expenses of Joshua’s ongoing medical care, as well as the upcoming birth of his first child. Mary Ann received $1,399.

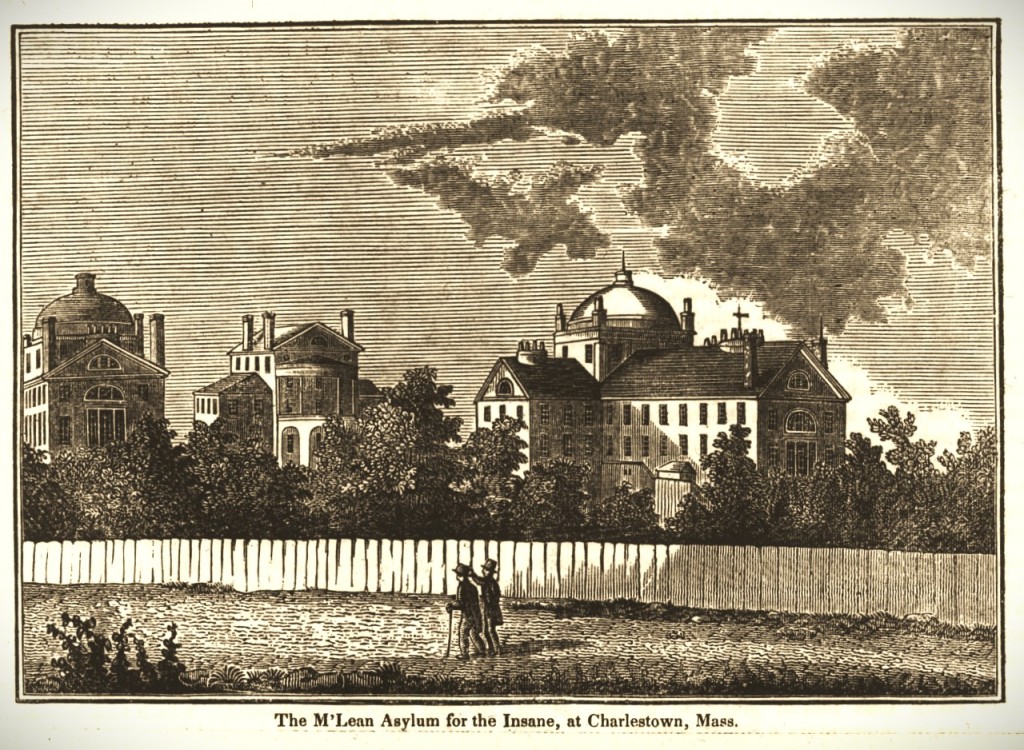

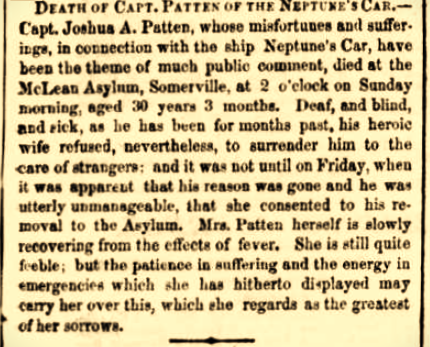

As commented by a journalist from the New York Daily Tribune, Mary Ann was soon widowed. Joshua died on July 26, 1857, at the age of 30, at McLean Asylum in Boston. He died blind, deaf, and completely unconscious. He didn’t even know that Mary Ann had given birth to his son, Joshua Patten Jr. On the day of his death, the port’s maritime flags flew at half-mast, and church bells tolled in his honor.

But the problems did not end. Shortly after, Mary’s father, who was also a sailor, was lost at sea.

Unfortunately, Mary Ann Brown Patten never fully recovered from the intense experience. In 1860, she also contracted tuberculosis. On March 17, 1861, at the young age of 23 years, 11 months, and 11 days, she died. She is buried in Boston next to her husband.

Memory

In Brazil, there is an idea that the United States is a nation that “highly values its history,” that the people there “are very patriotic,” and that it “gives a lot of value to its symbols and heroes.” However, in the case of Mary Ann Patten, this is not so!

Today, despite the significance of the events in 1856, this woman is primarily remembered for being recognized as the first woman to command a merchant ship in the United States. As a tribute to her, a hospital called Patten Health Service Clinic, in the Merchant Navy, bears her name. The Academy of that country is located in King’s Point, New York. And this happened more than 100 years after her accomplishment.

As far as I have researched, no American ship is named after her. Even during World War II, when the United States built an immense fleet of cargo ships, known as “Liberty ships,” with an astonishing total of 2,710 completed, none of them were named in honor of this woman. Several of these ships were named after women. I could be wrong, but I found no reference to her life being the subject of a Hollywood movie or documentary. I know she was the inspiration for a novel, but I haven’t found a more comprehensive literary work about her life.

But what happened to her in 1856 is something that should not be forgotten.